Talking about the latest Criterion DVD release has already landed me in a dustup, so I tread with caution. On Facebook I said the movie was a curio, not a lost classic. That prompted a critic whose work I regularly read to call me a ... well, the exact name was left vague but I’ll go with the most positive option and say philistine. The critic ultimately kicked me to the digital curb. Maybe Errol Morris is right when he suggests that social media is as bad as high school.

Bigger Than Life generated an uncommon amount of publicity when it debuted on video last week. The majority of reviews were laudatory; the word “masterpiece” crops up repeatedly. It was hailed as a neglected landmark, an incisive social critique, a scathing exposé of the American Dream.

All of which should have raised red flags. I don’t have many rules when it comes to movies, but here’s one: when every hosanna fawns over what a movie says but not what actually happens onscreen, odds are you’re in for a tough sit. Nicholas Ray directs. The movie is based on a New Yorker article and feels like it. James Mason plays a mild-mannered schoolteacher who moonlights as a taxi dispatcher. He suffers from increasingly frequent bouts of pain which are diagnosed as a symptom of a fatal arterial disease. But there’s a new treatment, the miracle drug cortisone. It saves Mason’s life, but also triggers manic episodes that crescendo into full-blown psychosis with his abuse of the drug. He becomes a suburban Nietzsche, a household tyrant terrorizing his family.

Nicholas Ray directs. The movie is based on a New Yorker article and feels like it. James Mason plays a mild-mannered schoolteacher who moonlights as a taxi dispatcher. He suffers from increasingly frequent bouts of pain which are diagnosed as a symptom of a fatal arterial disease. But there’s a new treatment, the miracle drug cortisone. It saves Mason’s life, but also triggers manic episodes that crescendo into full-blown psychosis with his abuse of the drug. He becomes a suburban Nietzsche, a household tyrant terrorizing his family.

The lopsided script is so focused on Mason and his largely one note fugues that the behavior of the other characters is rendered incomprehensible. His doctors aren’t held to account. As for Mason’s wife (Barbara Rush), I had to keep stepping out of the movie to backtrack her motivations. “I suppose if she thinks X, it makes sense she’d do Y.” Many critics claim Bigger Than Life is fundamentally about issues of class – novelist Jonathan Lethem, a great admirer of the film, offers 27 minutes of cultural background on the DVD – but the movie treats money obliquely. In a key scene, Mason holds up medical bills shot in such a way that I couldn’t tell what they were until he’d already put them down. Here’s another of my rules: if your characters’ actions are essentially prompted by subtext, you’ve failed as a dramatist.

I was interested enough in the story to track down the original article in the New Yorker’s archives. Berton Roueché’s “Ten Feet Tall,” published in September 1955, is an astonishing piece of reportage that answered every question raised by Bigger Than Life’s flawed script. To begin with, the schoolteacher’s wife has a far more substantial presence. During the period in question, she herself was incapacitated by sickness. Her husband’s adverse reaction to cortisone was compounded by his doctor’s refusal to discuss why he was altering the dosage. Here’s the teacher on his physician: “He believes in a minimum of explanation and a maximum of results. And, of course, I said nothing to my wife.” The bath scene that gives the movie its signature image – Mason’s reflection in a shattered mirror – comes from out of left field in the film. The incident in context is smaller and far more devastating.

Roueché’s article is a case study. So is Bigger Than Life, in how not to adapt material.

UPDATE: Jaime Weinman offers a terrific counterpoint to this post.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Movie: Bigger Than Life (1956)

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Movie: A Prophet (U.S. 2010)

Lots going on, so I’ll keep this brief: you need to see this movie.

It’s a brilliant, hard-hitting epic. Malik, a young French Arab, is thrown into prison for a six-year bid. Without family or friends on the outside, he’s prepared to face his fellow inmates alone – until he comes to the attention of the Corsican gangsters who run the joint ... and need another Arabic prisoner killed. The preparation for the hit and the job itself are ferociously intense. Soon Malik finds himself in a strange no man’s land, protected by men who don’t respect him and reviled by his own kind. So he does what any smart kid would do: he begins exploiting his benefactors, his enemies and the system, and slowly amasses power.

Tahar Rahim manages to chart the transformation of Malik’s character while nailing down the true hard case’s complete lack of affect; he becomes a new man without it ever registering in his face. Rahim is matched by Niels Arestrup as the aging kingpin who didn’t expect the world inside the prison’s walls to change, too. Jacques Audiard’s direction is supple without stinting on detail. Seek this brutal, relentless and powerful movie out.

Sunday, March 21, 2010

Related: Lonelyhearts, by Marion Meade (2010)/Five Came Back (1939)

They make an unlikely couple. Nathanael West, an author whose comic sensibility is so dark it can be difficult to find. And Eileen McKenney, a Midwestern girl whose big city adventures spawned a miniature empire.Theirs may not have been a “screwball world,” as author Meade subtitles her joint biography; West and McKenney both died too young in a car accident caused by West’s notoriously bad driving mere days before the debut of the play that would make Eileen’s exploits even more famous. But Meade’s telling has that tone. She writes with an informal, almost jaunty voice that suits what is ultimately a tale of kindred spirits finding each other, and prior to that a recounting of literary circles in 1920’s New York and ‘30s Hollywood. The most interesting material is about those orbiting the star-crossed twosome, like West’s overbearing mother and Ruth McKenney, the staunch Communist who gained her greatest fame chronicling her superficial sibling’s antics in My Sister Eileen (filmed twice, adapted into a play and later the musical Wonderful Town).

It’s the rare biography that makes you think less of its subject – well, one of them – but it happens here with West, who comes across as pretentious and scheming. Amazingly, a stint in the Poverty Row salt mines matured him. The Day of the Locust, with its parade of grotesques and apocalyptic sense of alienation, is a book I respect without actually liking. Give me the realistically grim but more humane work of West’s Republic Pictures stablemate Horace McCoy.

West’s greatest success as a screenwriter is, ironically, one of the first disaster movies. In Five Came Back he mixed disparate types – among them a gangster’s young son, his pistol-packing “uncle,” an anarchist and the lawman escorting him to his execution, plus Lucille Ball as a woman who’s been around the block with an EZ Pass – on a doomed airplane. Spoiler alert: five come back. The film plods in its early stages, serving as a better showcase for director John Farrow than West. But tropes become tropes for a reason. Once the plane crashes and the action moves to the jungle, the stock characters become more involving. West, expecting to receive sole credit, was dismayed to find himself sharing space with, among others, Dalton Trumbo, who transformed the anarchist villain into the voice of reason.

The film plods in its early stages, serving as a better showcase for director John Farrow than West. But tropes become tropes for a reason. Once the plane crashes and the action moves to the jungle, the stock characters become more involving. West, expecting to receive sole credit, was dismayed to find himself sharing space with, among others, Dalton Trumbo, who transformed the anarchist villain into the voice of reason.

Five Came Back was the sleeper hit of 1939, launching Farrow to the A-list. (ASIDE: Want to read about Farrow’s glory days? I wrote an article about them that’s in this book.) He would remake the film nearly 20 years later as Back From Eternity. Guess what else is on my DVR?

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Book: The Detective in Hollywood, by Jon Tuska (1978)

If I’ve learned one thing from the big dogs of the noir circuit, it’s the importance, nay, the necessity of documentation. Talk directly to the people who made the movies, get them on the record, create a body of knowledge. (Exhibit A, as I’ve said before: Eddie Muller’s one-of-a-kind Dark City Dames.)

That’s what makes Jon Tuska’s overview of the private eye genre so vital. He did the legwork when there were still plenty of people around to interview, like Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Montgomery.

Even more impressive is that he committed to this undertaking in those dimly remember’d days before video and the internet, when research of this kind meant hard work. Tuska sat down with Lloyd Nolan, who played Michael Shayne, and Nolan brought along something a fan sent that might be helpful: a typewritten list of all of Nolan’s films. An asterisk by the title meant the fan owned a print of the movie.

Tuska’s work is exhaustive but never tiring, guiding you through now-neglected series like the Crime Doctor and Mr. Wong, telling you which Charlie Chan films are worth your while. The chapter on The Thin Man movies also includes their many imitators. Tuska writes with wit and affection, but also a sharp critical eye. Some of his positions I agree with (dismissing all of Boston Blackie), some I don’t (no way is The Drowning Pool better than Harper). And the few stances he cheerily admits are heretical – such as claiming that Montgomery’s subjective camera Lady in the Lake is superior to both Murder, My Sweet and The Big Sleep – are so persuasively argued that I’m willing to give the movies in question another look. The book ends with an affectionate appraisal of the ‘70s troika of The Long Goodbye, Chinatown and The Late Show.

I first learned about the book from Ed Gorman, who wonders why it never got its due. Having read it, I’m now asking the same question. Tuska updated it in 1988 as In Manors and Alleys: A Casebook on the American Detective Film. I’m going to need a copy of one version or the other to call my own. Any fan of The Whistler is welcome around here.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Book: I Should Have Stayed Home, by Horace McCoy (1938)

One of the knocks on e-readers that baffles me is, “You lose that new book smell!” To which I say, “What about that old book smell?” A few years ago I picked up a paperback in an antique store containing two novels by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding. It was only when I got the book home that I realized it reeked, as if it had been used to prop up a leaky boiler in a basement that doubled as a hobo graveyard. Rosemarie, her eyes watering in the next room, announced, “Either you read that one outside or you don’t read it at all.” As I consigned the leathery pages to the flames, I heard them cry out in torment. (Actually, I just tossed the book in the trash. Several blocks away.)

Since buying my Kindle, I’ve been primarily filling it up with older, somewhat hard to find books. Solomon’s Vineyard and Fast One did not disappoint. Nor did Horace McCoy’s brief and brutal I Should Have Stayed Home. McCoy, a journalist and Black Mask writer, moved to Los Angeles in 1930 with hopes of becoming an actor. He would instead become a screenwriter. But the cattle call experience marked his work, especially his best known novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, about Hollywood aspirants participating in a grueling dance marathon, and I Should Have Stayed Home.

McCoy, a journalist and Black Mask writer, moved to Los Angeles in 1930 with hopes of becoming an actor. He would instead become a screenwriter. But the cattle call experience marked his work, especially his best known novel, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, about Hollywood aspirants participating in a grueling dance marathon, and I Should Have Stayed Home.

Georgia-born Ralph Carston headed west with dreams of stardom, but he finds himself short of cash, scuffling for extra work, and sharing a seedy bungalow with his Platonic roommate Mona Matthews. A friend of Mona’s is arrested for shoplifting. A chain of circumstance follows that brings Ralph in contact with an older woman who has designs on him, a disillusioned flack, and a host of other Tinseltown types.

It’s a grim, powerful book. Ralph seethes with desperation and rage. He’s implied in his letters to his mother that he’s already made it in Hollywood, but he soon learns that his accent and his attitude may keep him from success. Scarier is the resentment boiling over into hatred that he feels toward those who have managed to grab the brass ring. (“It made me sore, sitting here looking at Robert Taylor, the biggest star in the pictures, trying to figure out what he had that put him where he was and that, goddam it, one of these days ...”) It’s an unsparing look at the dark reality of show business that deserves to be mentioned alongside Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust.

Saturday, March 06, 2010

Miscellaneous: Your Weekend Recommendations

Now that Noir City has wrapped, it’s high time for me to get my head back in the twenty-first century. Here are some more contemporary picks. Wake Up Dead, by Roger Smith (2010). Roxy Palmer used to be an American model. Now she’s living in Cape Town, South Africa, trophy wife to an arms trafficker. When two street punks jack their car, Roxy takes advantage of the situation. Thus setting into motion a tortured Elmore-Leonard-meets-Robert-Altman chain of events embroiling Roxy, the carjackers, a mercenary known as Billy Afrika, a psychotic gang boss hell-bent on a reunion with his prison “wife,” and an honest bastard of a cop named Maggott forced to investigate with his son in tow.

Wake Up Dead, by Roger Smith (2010). Roxy Palmer used to be an American model. Now she’s living in Cape Town, South Africa, trophy wife to an arms trafficker. When two street punks jack their car, Roxy takes advantage of the situation. Thus setting into motion a tortured Elmore-Leonard-meets-Robert-Altman chain of events embroiling Roxy, the carjackers, a mercenary known as Billy Afrika, a psychotic gang boss hell-bent on a reunion with his prison “wife,” and an honest bastard of a cop named Maggott forced to investigate with his son in tow.

The bleakness of this book is, at times, suffocating; each character’s history is so grim that the miasma of misery threatens to become blackly comic. But there’s no denying that every one of Smith’s players pops off the page, and his pacing is relentless. It’s a prison shank of a novel: brutal and hard, driving in deep and leaving a hell of a mess.

The Ghost Writer (2010). A review described Roman Polanski’s adaptation of Robert Harris’ novel as a “town car thriller.” That how it seems for much of its running time, a well-appointed and smooth ride.

Ewan McGregor is the title character, hired to punch up the memoirs of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair Adam Lang (Pierce Brosnan). As Lang is brought up on charges in The Hague for his role in abetting America’s rendition program, the ghost begins to wonder about the mysterious suicide of his predecessor.

There are terrific performances throughout, including one from 94-year-old Eli Wallach. The movie’s final revelation is a doozy, delivered in an extended, largely wordless set piece that is a joy to behold. Sly, meticulously constructed, with a perfect visual capper. Days later, I’m still cackling at it.

Wednesday, March 03, 2010

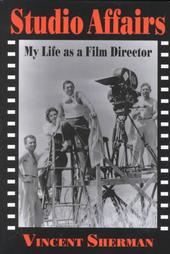

Miscellaneous: Sherman’s March

Vincent Sherman had a solid career as a director, making melodramas (Mr. Skeffington, The Hasty Heart) and films of a darker, noirish hue (The Hard Way, Nora Prentiss, The Damned Don’t Cry). But he should be remembered for his autobiography Studio Affairs, one of the most honest and therefore best books about Hollywood ever written. Let’s get the prurient stuff out of the way, shall we? Sherman slept with several of his leading ladies and details those relationships. The dalliances strangely parallel each actress’s films; Bette Davis’ is histrionic with a tragic ending, while Joan Crawford’s is brazen and tawdry. (His one night stand with Rita Hayworth is simply sad.) What emerges from the telling is an astonishing portrait of a lasting marriage; Sherman’s wife Hedda knew of his affairs and even became friends with Crawford.

Let’s get the prurient stuff out of the way, shall we? Sherman slept with several of his leading ladies and details those relationships. The dalliances strangely parallel each actress’s films; Bette Davis’ is histrionic with a tragic ending, while Joan Crawford’s is brazen and tawdry. (His one night stand with Rita Hayworth is simply sad.) What emerges from the telling is an astonishing portrait of a lasting marriage; Sherman’s wife Hedda knew of his affairs and even became friends with Crawford.

Sherman is every bit as meticulous when it comes to recounting his professional life. Studio Affairs lays bare how many compromises are necessary for a career in Hollywood, how frequently opportunities fade away. Sherman never forgot his training in the B-movie unit at Warner Brothers, where previous years’ prestige projects were repurposed into programmers. (The first half of The Mayor of Hell plus the end of San Quentin became Crime School, Sherman’s first writing credit.) When a projected adaptation of James M. Cain’s Serenade fell apart, he reworked The Letter into The Unfaithful.

After reading the book, I caught up with a few Sherman films on DVD. All Through the Night (1941) was of particular interest; Humphrey Bogart in an anti-Nazi action comedy? He plays gambler Gloves Donahue, whose efforts to find out what happened to his favorite cheesecake – I am completely serious – lead him to a ring of fifth columnists. Bogart’s gang includes Jackie Gleason and Phil Silvers. And yet somehow, the movie is leaden from the jump. Honestly, it’s dreadful. I only kept watching because I was convinced it had to get funnier.

Still, it does produce my favorite story in Sherman’s book. Peter Lorre, as one of the Nazi spies, has to shoot a lock off a door while Judith Anderson hollers in German behind him. When Sherman requested a second take, Lorre says, “That’s all, brother Vince. I can only do this kind of crap once a day. Besides, it’s six o’clock. Time to go home.” (Can’t you just hear Lorre saying that?) Sherman asks how, if that’s true, Lorre could have made all those Mr. Moto pictures. Lorre retorts, “I took dope!” Later, Sherman learns that Lorre wasn’t joking.

Next up was the movie that cemented Sherman’s reputation. Underground (1941) was meant to be a B-picture, but a strong script and Sherman’s direction made it a surprise hit. A wounded Nazi soldier, loyal to the party, returns home, not realizing that his older brother is a leader of the resistance. They are quickly set on a collision course.

Propaganda? You bet. Effective? And how, especially that ending. The idea that this movie was in theaters months before Pearl Harbor boggles the mind. First and foremost, though, Underground functions as a gripping thriller.

Another good Sherman story: the role of an elderly man who aids the resistance was reconceived for the gorgeous Mona Maris because she was “friends” with the film’s producer – and if he didn’t cast her, she was going to cut up all of his suits. Maris is terrific in the movie, but Sherman never bought her in the part.